|

In 1856, two dispirited young Germans headed to their home base in London from Lake Boga near Swan Hill, their mission declared a failure. Andreas Täger and Friedrich Spieseke had left Germany five years earlier, fired with a passion to teach the Christian faith to the Aboriginal people of Australia.

Encouraged by Governor La Trobe, a fellow member of the Moravian Brethren Church who shared the vision and set land aside at Lake Boga, they set about building a mission station to both protect and educate the Wemba Wemba people. Their ambitions were high and their spirit genuine, but many things conspired to erode their manful efforts. But were they failures? Click on Read More to hear more of the story of Lake Boga. Recently, when I attended a Cornerstone Community gathering in Swan Hill, I was privileged to witness a baptism at Lake Boga. Young men are still stepping out to take commitment to Jesus seriously .

1 Comment

I was recently writing a piece for The Western Herald in Bourke when I stumbled onto a century-old Christmas postcard that whispered a remarkable story. Unlikely as it may seem, the card links Australia’s most famous naval engagement to its most inland port. I’ll try to piece a narrative together from the fragments that remain.

When war was declared in 1914, the 33,000 people of German origin living in Australia were forbidden to leave the country without a permit and ordered to report to police. Many of them were Lutheran Christians who had originally migrated seeking religious freedom and created hard-working farming communities in South Australia’s Barossa Valley. As the casualty lists from Gallipoli lengthened during 1915 and anti-German feelings grew more intense, the Great War came home to remote outback Bourke. German civilian prisoners of war were shipped to Australia from Singapore, Ceylon, Borneo, New Caledonia, Fiji, New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. A hundred or so were deposited in empty houses in the town. Every December, I sit down with Ebenezer Scrooge, “…a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, clutching, covetous old sinner” as Charles Dickens described him. The image of the lonely, tight-fisted miser growling “Bah, humbug!” at anyone daring to draw him into the spirit of Christmas, is etched deep into the imagination of the Western World. Along with dozens of other equally vivid characters, Scrooge made Dickens the rock-star storyteller of the 19th century.

The 100-page story A Christmas Carol has been credited with launching the modern celebration of feasting and family that dominates the year’s end all across the globe. What’s mostly forgotten is the fact Dickens designed it as a parable of redemption and I’m sure that’s the magnetism that has tugged at me every Christmas for fifty years or more. It's a ghost story with a difference. When you drive streets in Maclean lined with tartan telegraph poles and hear the skirl of the bagpipes echoing in the main street, you know the town is definitely a stronghold of Australia’s Scots history. And mine for that matter. Over two million of us claim Scots ancestry – my grandchildren have the blood of the Baird, Carey, Murray and McDonald clans in their veins.

So, I spent a day or two there recently, looking under the ancestral kilt to see why big numbers of Scots moved here in the mid-1800’s. I was heartened to discover that the claim we Australians make for having one of the best lifestyles in the world, could well have been built on a bedrock of purposeful duty to God mined out of bare hills and heather half a world away in Scotland. Sitting at the impressive polished table in the School of Arts building in the New England town of Tenterfield, I wondered just how this remote country town, straddling the train line between Sydney and Brisbane, became a crucial link in Australia’s journey to nationhood.

I discovered it has to do with one strong-minded man – Henry Parkes. Right where I was sitting was the spot from which the feisty, five-time Premier of NSW first gave a rousing speech, which he then repeated fifteen times in other locations. This gave serious momentum to the push for federating the six states. Professor Marie Bashir, the recent Governor of this state, declared “…his stirring words of exhortation and unity to the crowd of citizens who loved him – ‘One people, one destiny’ – will continue to inspire.” As I travel, I look out for the stories and symbols that shape us Aussies. Observers say that during the first few years of our lives as we learn to talk, to read, to share in the common story of our people, we’re quietly absorbing a worldview.

Normally we’re not conscious of it. It’s like the lenses of our glasses, it is not something we look at, but something through which we look in order to see the world. On the road to Gundagai, I discovered a faithful hound, a popular song and an inspirational sculptor that had all played a part in telling us about ourselves. Robyn and I sat in a palliative care room last week and witnessed first hand the two nurses ministering to our friend and her family. “This is our passion” one of them told us. That affirmation echoed what I heard in the voice of Katherine, a paediatric care nurse in Wagga, a few weeks earlier.

The historian in me couldn’t help seeing behind these kind women, the figure of Florence Nightingale, who almost single-handedly transformed the role of nurses in the hospital in Scutari during the Crimean War of 1852-56. Others had gone before her but this Christian woman made caring a world-wide calling – a true profession. We've had some pretty wild weather lately and travelling home through some heavy downpours, we decided to take time out in the town of Yass in southern NSW. It was a great opportunity to seek out a story. We headed first to the Tourist Centre, had a bit of a walk around town and then hunkered down in the local library for a while. Here's the story we discovered.

Last night the throb of Harley-Davidsons announced the Longriders had come to Dubbo. After meeting their club Chaplain in Uralla in March we invited them to visit if they came through Dubbo. We also figured they would have something in common with Bruno Efoti’s Tradies Insight group. It turns out they are both working to provide the kind of spaces where men in particular are comfortable enough to be themselves and talk out life issues. WATCH as Paul chats with Padre Matt about their experience.

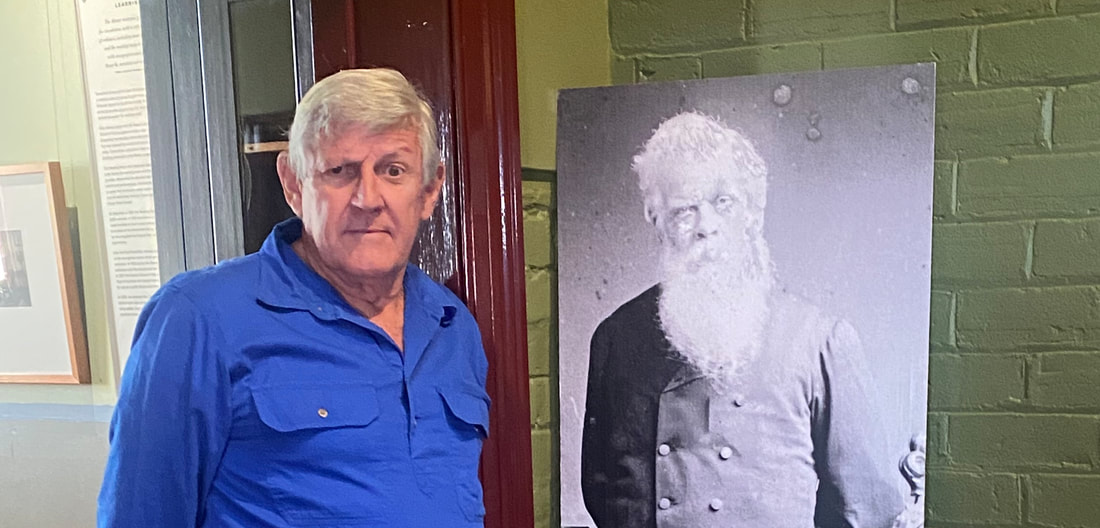

This is the story of an Irish youth who arrived in Australia with nothing and died giving away a to benefit orphans, schools, universities, hospitals and churches. Samuel McCaughey was a genius. In the world of 19th century agriculture he fathered large scale irrigation works, was an innovator in the wool industry, designed and built earth moving equipment and was on the cutting edge of new technology. His vast sheep stations were among the largest in the world and featured beautifully built homesteads and out buildings - again of his own design. WATCH as Paul tells his story.

|

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed