|

In 1856, two dispirited young Germans headed to their home base in London from Lake Boga near Swan Hill, their mission declared a failure. Andreas Täger and Friedrich Spieseke had left Germany five years earlier, fired with a passion to teach the Christian faith to the Aboriginal people of Australia.

Encouraged by Governor La Trobe, a fellow member of the Moravian Brethren Church who shared the vision and set land aside at Lake Boga, they set about building a mission station to both protect and educate the Wemba Wemba people. Their ambitions were high and their spirit genuine, but many things conspired to erode their manful efforts. But were they failures? Click on Read More to hear more of the story of Lake Boga. Recently, when I attended a Cornerstone Community gathering in Swan Hill, I was privileged to witness a baptism at Lake Boga. Young men are still stepping out to take commitment to Jesus seriously .

1 Comment

If you’ve heard ‘The Old Rugged Cross’ played on the gumleaf, you never forget it. I first heard it standing under the ghost gums that stood stark white against the ochre walls covered in the rock art of the Ngemba people. I was leading a tour group at Mt Gundabooka, a rugged range that lies like a goanna on the horizon South of Bourke.

The musician was Bill Reid, a pastor of the United Aboriginal Mission, who winked at me from under the tilted brim of his Akubra, quietly selected a leaf, cupped it between his knotted shearer’s hands and began to play. The intrigued tour group eagerly gathered around. That moment is etched in my mind – Pastor Bill, white haired and erect, playing a song of Christian faith in a canyon that had echoed to clapsticks and corroboree of Aboriginal people for many centuries. This weekend’s AFL indigenous round is named for Sir Douglas Nicholls. Australian Football’s webpage makes a significant comment about the champion Fitzroy footballer, “Arguably one of the most famous, and undeniably among the most important, Australians of the 20th century, Doug Nicholls' most significant accomplishments transcended football.”

What were they? A few weeks ago, I stood in the humble weatherboard schoolhouse at Cummerugunga where a young Douglas had hidden under the floorboards for fear of the police who were taking the young girls away to the Cootamundra Girls Home. In later life, he said that Jesus’ message of forgiveness enabled him to rise above bitterness. You could be forgiven if, like me, you’ve watched war movies over the past fifty years and got the impression that square-jawed, bullet-proof commandos were the only heroes on the battle front. Padres? Well, they were inoffensive chaps who kept well back from the action.

Michael Gladwin’s book ‘Captains of the Soul’ blows that myth to smithereens. His extensive research declares that the weapon-less chaplains were, more often than not, men admired by the troops for their calibre and courage. Photographer George Silk remarked on the toughness of the padres. Of this photograph of a Catholic chaplain conducting mass prior to battle, he wrote, “You could almost see God Himself in the jungle.” Digest this astonishing story Gladwin tells of a chaplain putting his life on the line to bury a young Digger. Australia should be proud of the fact that Lifeline began here as the initiative of the Rev Sir Alan Walker. This Methodist minister was fearless at speaking out on things that matter and relentless at working on solutions to the things that trouble us. My friend Ian Palmer who volunteers as a telephone counsellor sent me his reflections on what this 24/7 service has meant for us over the past six decades and OK’d me to share it. It’s an amazing story.

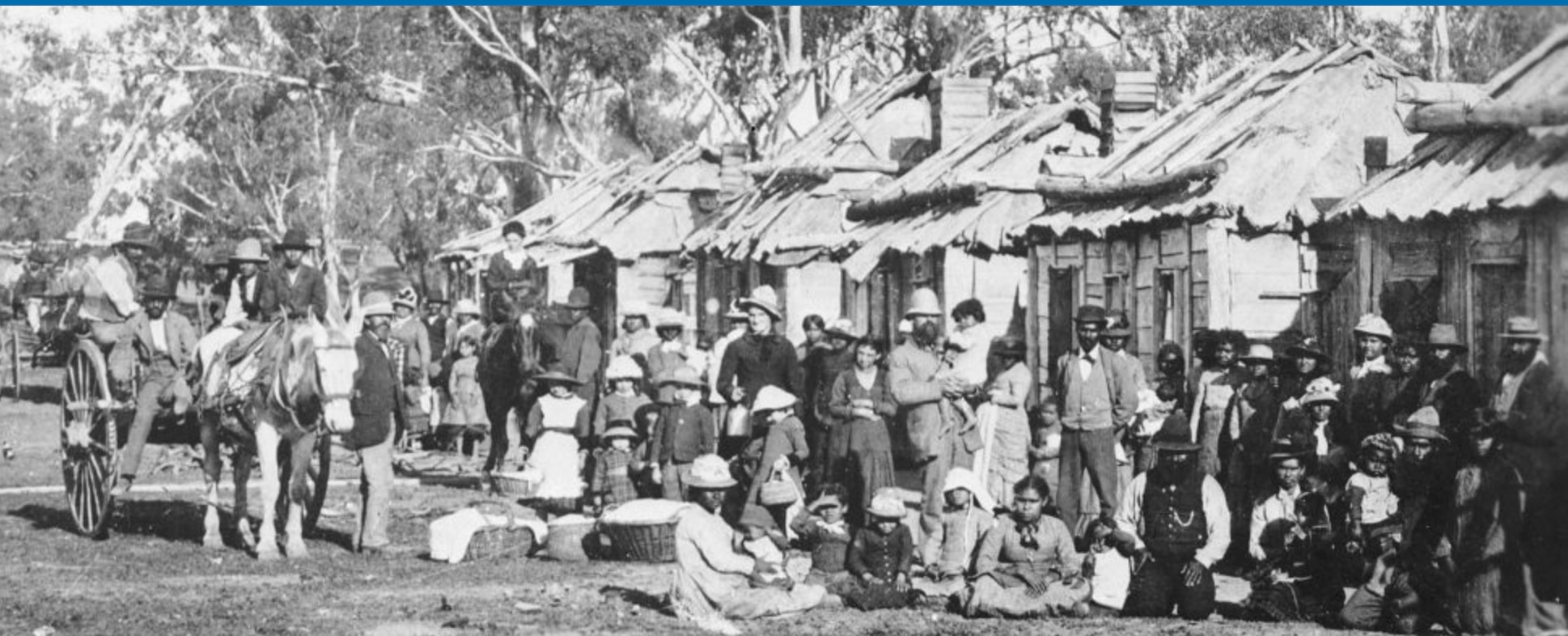

I had been looking forward to visiting Echuca for a while because it’s the site of one of the greatest of Australia’s invisible faith stories. Back in the 1870’s Daniel and Janet Matthews, without support from any church or society, created a sanctuary for the suffering and hunted Aboriginal people. They called it Maloga.

Located on a beautiful bend of the Murray River, this traditional ceremonial ground saw leaders emerge from the Yorta Yorta people who learned to make the teachings of Jesus a launching pad for the civil rights movement that finally gave them recognition as citizens in their own country. On return to Adelaide after being wounded in fighting missions over the trenches of the Western Front in World War One, Captain Harry Butler cast a vision for aviation in Australia. “The plane was great in war, but it will be greater in Peace. This…is the beginning of a new era in mail and passenger transport.” To demonstrate, in 1919, he pioneered the world’s first over-water airmail flight in his crimson Bristol MC fighter plane The Red Devil, flying from Adelaide to his hometown on the Yorke Peninsula in South Australia. It was a breathtaking achievement and he quickly drew wondering crowds to watch his daring stunt flying.

Many restless young airmen like Harry finished the war looking for further challenges. Englishman Len Daniels, who had earned his wings piloting bi-planes dubbed ‘the flying bedsteads’ with the Royal Flying Corps in Egypt, arrived in Australia in 1922, in search of a better climate and a theatre to match his passion to be an active missionary. The newly formed Bush Church Aid captured his interest. The Bush Missionary Society began in 19th century Sydney with a handful of boys reaching out ten miles to Coogee and Five Dock – the remote bush as it was then. Les Stewart stretched the thinking and the boundaries of the mission first to Western Australia and then asked his board’s permission to venture 12,000 km to Siberia, Central Russia and Uzbekistan. Now that’s really going bush!

Les wasn’t daunted by the physical challenge, but more by the fact that the autocratic regimes of these countries resist the Christian message. But his heart heard these oppressed Christians calling for help. Here he tells heart-stopping stories of the way he negotiated his visits there to teach hungry congregations. The villages at Burrill Lakes and Termeil made headlines when they were caught in the holocaust of 78,000 hectares of bush ablaze in 2019. Les Stewart was trapped in a creek bed with fire all around, his clothes smouldering, trying to defend his homestead, when his son arrived in a water-tanker and hosed him down.

It was a narrow escape, but not the first for the man singer/song-writer Colin Buchanan christened, ‘The Bishop of Burrill.’ Les is a surfer, a horseman, a bikie and a preacher. More than anything, this bushman is a doer. Most of his life has been given in the service of people in remote places as a leader in the Bush Missionary Society. I learned from him that this grew from the initiative of a handful of teenage boys back in the 1850’s, taking simple leaflets explaining the Christian faith to isolated people on the fringes of Sydney. In a short time, missioners in horse-drawn vehicles were travelling all across NSW, an area four times the size of the United Kingdom, connecting to families and itinerants on lonely back-country properties. Last night the throb of Harley-Davidsons announced the Longriders had come to Dubbo. After meeting their club Chaplain in Uralla in March we invited them to visit if they came through Dubbo. We also figured they would have something in common with Bruno Efoti’s Tradies Insight group. It turns out they are both working to provide the kind of spaces where men in particular are comfortable enough to be themselves and talk out life issues. WATCH as Paul chats with Padre Matt about their experience.

|

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed