|

In 1856, two dispirited young Germans headed to their home base in London from Lake Boga near Swan Hill, their mission declared a failure. Andreas Täger and Friedrich Spieseke had left Germany five years earlier, fired with a passion to teach the Christian faith to the Aboriginal people of Australia.

Encouraged by Governor La Trobe, a fellow member of the Moravian Brethren Church who shared the vision and set land aside at Lake Boga, they set about building a mission station to both protect and educate the Wemba Wemba people. Their ambitions were high and their spirit genuine, but many things conspired to erode their manful efforts. But were they failures? Click on Read More to hear more of the story of Lake Boga. Recently, when I attended a Cornerstone Community gathering in Swan Hill, I was privileged to witness a baptism at Lake Boga. Young men are still stepping out to take commitment to Jesus seriously .

1 Comment

If you’ve heard ‘The Old Rugged Cross’ played on the gumleaf, you never forget it. I first heard it standing under the ghost gums that stood stark white against the ochre walls covered in the rock art of the Ngemba people. I was leading a tour group at Mt Gundabooka, a rugged range that lies like a goanna on the horizon South of Bourke.

The musician was Bill Reid, a pastor of the United Aboriginal Mission, who winked at me from under the tilted brim of his Akubra, quietly selected a leaf, cupped it between his knotted shearer’s hands and began to play. The intrigued tour group eagerly gathered around. That moment is etched in my mind – Pastor Bill, white haired and erect, playing a song of Christian faith in a canyon that had echoed to clapsticks and corroboree of Aboriginal people for many centuries. This weekend’s AFL indigenous round is named for Sir Douglas Nicholls. Australian Football’s webpage makes a significant comment about the champion Fitzroy footballer, “Arguably one of the most famous, and undeniably among the most important, Australians of the 20th century, Doug Nicholls' most significant accomplishments transcended football.”

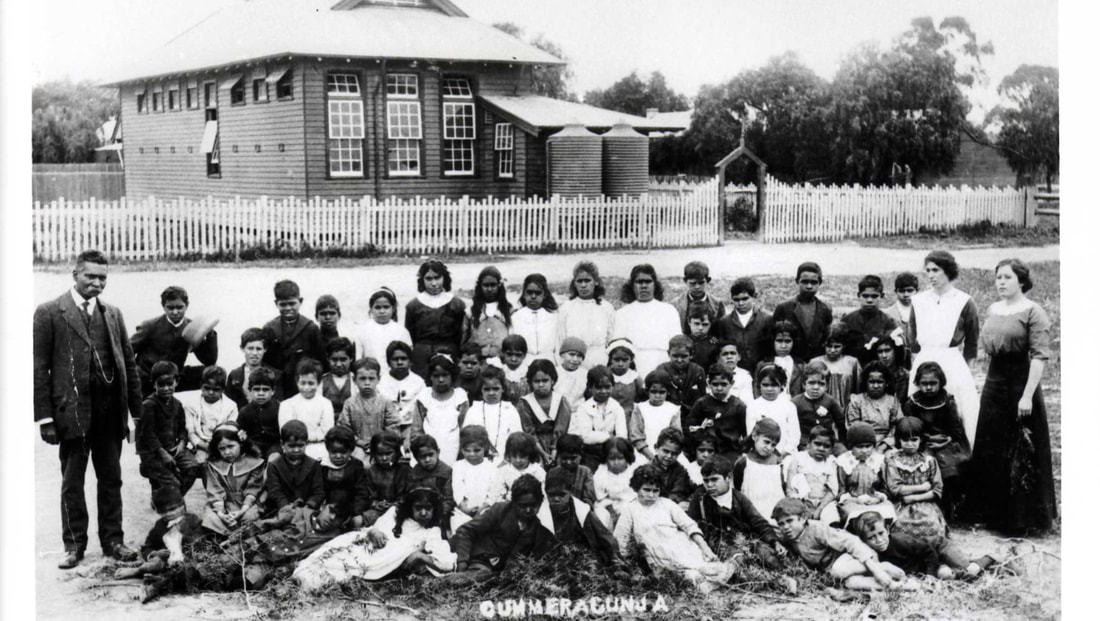

What were they? A few weeks ago, I stood in the humble weatherboard schoolhouse at Cummerugunga where a young Douglas had hidden under the floorboards for fear of the police who were taking the young girls away to the Cootamundra Girls Home. In later life, he said that Jesus’ message of forgiveness enabled him to rise above bitterness. Jesus shook the accepted cultural prejudice of his people with his story of road-side kindness. The hero who stopped to help the victim of gang-violence was a man from neighbouring Samaria that his listeners considered a total outsider. Jesus was offering an open challenge to the strict orthodoxy of his audience. He knew they would never have dreamed of putting the words ‘good’ and ‘Samaritan’ together. The tale of this anonymous rescuer was so impactful, it has fixed the phrase ‘good Samaritan’ permanently in the English language as a term that speaks of surprising, unexpected generosity.

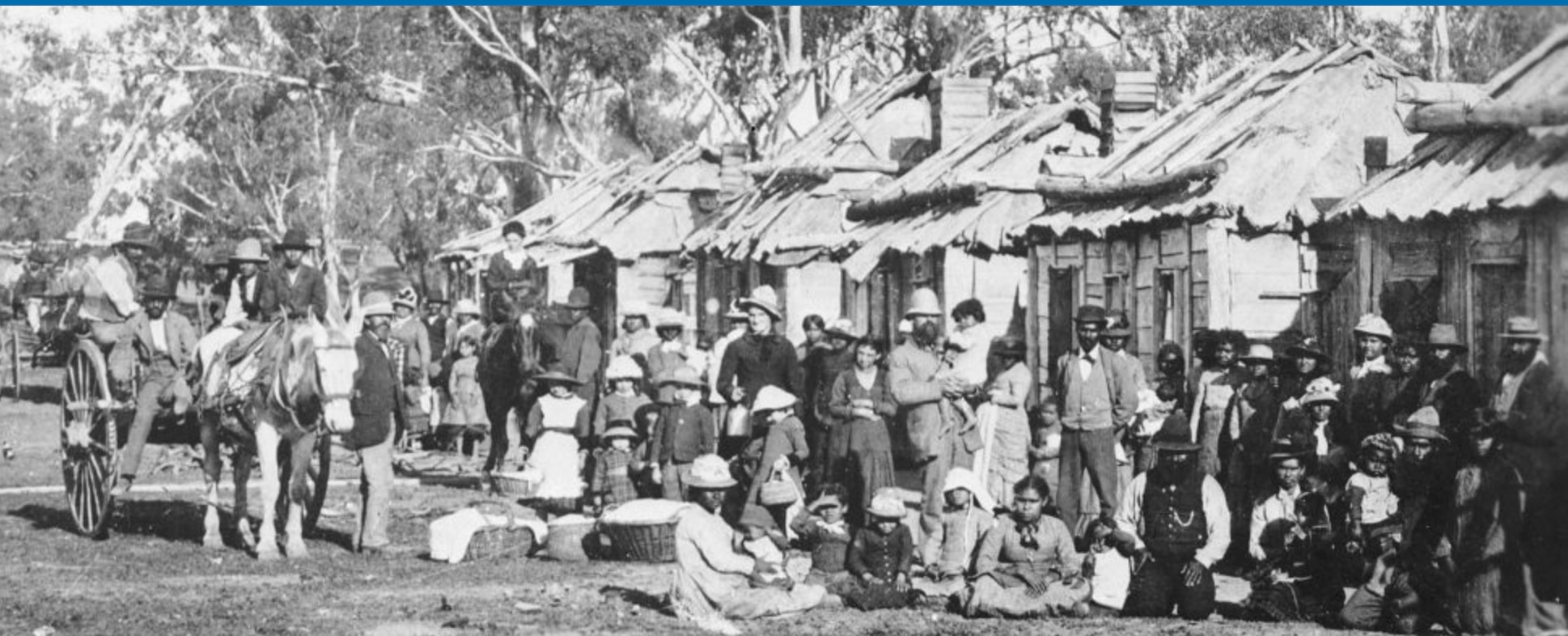

A few years ago, the southern NSW country town of Gundagai enshrined a muscular version of a similar story in their town centre. The striking bronze memorial celebrates Yarri and Jacky Jacky, two tribesmen from the local Wiradjuri people, who ferried an astonishing 69 people to safety when the town was swept away by a raging Murrumbidgee River in 1859. They were assisted by other Aboriginal people, including Long Jimmy and Tommy Davis. I had been looking forward to visiting Echuca for a while because it’s the site of one of the greatest of Australia’s invisible faith stories. Back in the 1870’s Daniel and Janet Matthews, without support from any church or society, created a sanctuary for the suffering and hunted Aboriginal people. They called it Maloga.

Located on a beautiful bend of the Murray River, this traditional ceremonial ground saw leaders emerge from the Yorta Yorta people who learned to make the teachings of Jesus a launching pad for the civil rights movement that finally gave them recognition as citizens in their own country. Cummeragunja sits on a sweeping bend of the Murray River about 20km upstream from Echuca. It’s home to some significant chapters of the Christian experience of the Yorta Yorta people. I’ve already posted the story of the remarkable Thomas Shadrach James, who taught a generation of Aboriginal activists to ‘lead and write.’ It was good to stand in the schoolroom of that dedicated Mauritian Indian teacher who quietly helped change the course of history for the Aboriginal people. Two of his trainees - Doug and Gladys Nicholls - are buried side by side out on the sand ridge and it was an honour to pay our respects there to these two outstanding Australians. I’ve told their story on this Outback Historian website. I think these people made Cummeragunja a genuinely sacred site. Look out for more stories related to this place.

In December 2007, a crowd of 500 people outside Victoria’s Parliament building gave a lengthy applause as of one of Australia’s most unusual statues was unveiled. The bronze figures of a husband and wife stand arm in arm – he with a welcoming smile, an open stance and a hand extended – she, erect beside her man, looking at him with an expression of love and pride.

Sculptor Louis Lamen had gifted Australia with a warm and lasting image of one of the most unique teams in its history. A journalist dubbed them ‘a compelling double act’ and he was right – they were! The memorial describes them as, ‘River People who turned the tide of history and injustice to progress the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This is the first memorial statue in Melbourne dedicated to two Aboriginal community leaders, Pastor Sir Doug and Lady Gladys Nicholls. They vigorously fought for the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across this country and are an eternal symbol of our ongoing history and commitment to human rights in Australia.’ This is the story of a humble teacher who turned a wooden building on the Murray River into a kind of bush university – one that grew leaders who changed Australia. Thomas Shadrach James, was born in 1859 in Mauritius, an island off the coast of Africa known for its diverse racial make-up, mixed cultures and variety of religious faith. His parents were poor people determined to educate their children. His father worked his way from being an indentured labourer to serving as an interpreter for the British colonial government and a teacher in the Anglican Church. So, it’s no surprise that at the age of fourteen, Thomas was tutoring other boys and fluent in French, English and Tamil.

Discouraging family events drove 20-year-old Thomas to leave home to seek his fortune alone in Australia. His obvious ability saw him enrolled in medicine at Melbourne University in 1880, but a bout of typhus left him with shaking hands. The new immigrant made a disconsolate figure walking Brighton Beach on Port Phillip Bay on January 3rd 1881, his aspiration to be a surgeon shattered. READ MORE ... This photo tells a story.

This week my son Chris presented Riverbank Frank Doolan with an artwork he’s done of Bill Ferguson – he’s the bronze figure in the picture. The painting is Chris’s version of the famous photo taken of Bill standing in Elizabeth street in Sydney on Australia Day 1938 with a group of supporters. His quiet but forceful protest called attention to the sad fact that the Aboriginal peoples of our country were yet to be recognised as citizens. There are other stories hidden behind this photo. READ MORE ... Aunty Pat Doolan is one of those rare people you meet in life who radiate goodness. As a result she’s been a game-changer wherever she’s lived. You can’t help being touched by her rare blend of determination and kindness - that’s how she’s got things done. She leads by being a servant and she never wavers in declaring her faith in public.

|

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed