|

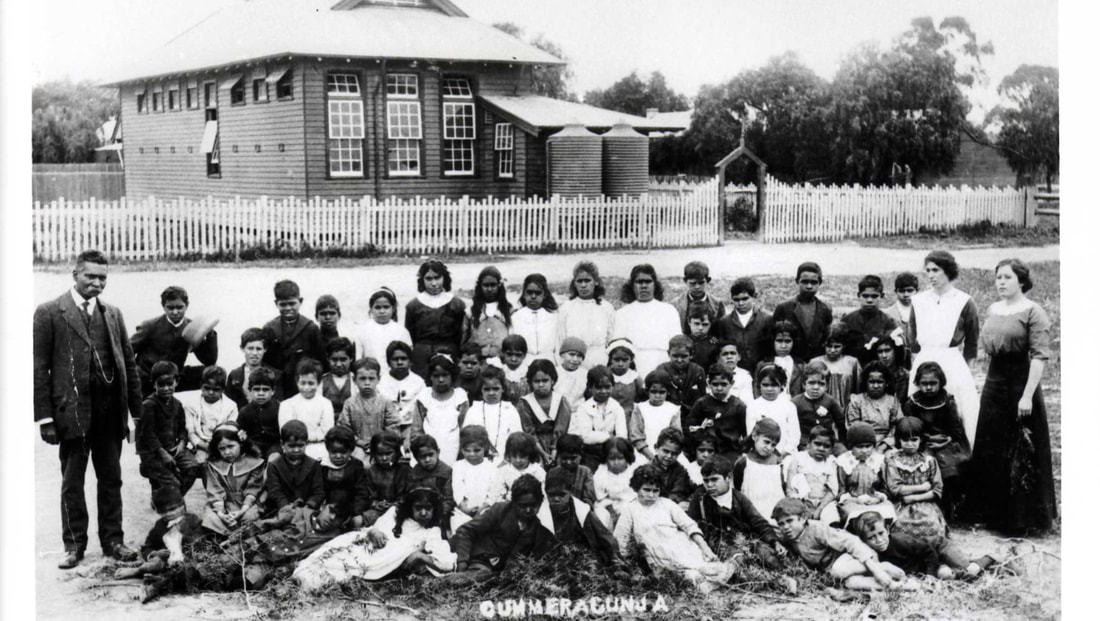

This is the story of a humble teacher who turned a wooden building on the Murray River into a kind of bush university – one that grew leaders who changed Australia. Thomas Shadrach James, was born in 1859 in Mauritius, an island off the coast of Africa known for its diverse racial make-up, mixed cultures and variety of religious faith. His parents were poor people determined to educate their children. His father worked his way from being an indentured labourer to serving as an interpreter for the British colonial government and a teacher in the Anglican Church. So, it’s no surprise that at the age of fourteen, Thomas was tutoring other boys and fluent in French, English and Tamil. Discouraging family events drove 20-year-old Thomas to leave home to seek his fortune alone in Australia. His obvious ability saw him enrolled in medicine at Melbourne University in 1880, but a bout of typhus left him with shaking hands. The new immigrant made a disconsolate figure walking Brighton Beach on Port Phillip Bay on January 3rd 1881, his aspiration to be a surgeon shattered. READ MORE ... The sound of voices singing led him to a group of Yorta Yorta people from Maloga Mission on the Murray River, led by Echuca businessman Daniel Matthews. Every year they camped in a field and held Christian services in a marquee to which the general public was invited. Part of Matthews’ purpose was to confront Melbourne citizens on a fashionable beach with indigenous people who had chosen to follow Jesus – the Jesus who had called out the injustices of his day. The singers were a remnant of the original 15,000 Murray River Aboriginals with lives shattered by diseases, brutal reprisals and starvation after having their hunting grounds over-run. Daniel and Janet Matthews were a compassionate couple who believed that God created all people of one blood and all were equally deserving of his blessings. In 1847 Daniel and his brother had funded and built a settlement, which became one of the only safe places in NSW for hunted native Australians. They were among the first colonisers to believe that these displaced people were capable of receiving a formal education. The young Indian student had experienced the power of learning to elevate a person of low caste and was moved by what he heard at the meeting. He said simply, ‘I felt the Lord call me that day.’ He volunteered to be their teacher and left Melbourne to become tutor and spiritual guide of the Yorta Yorta people. It was the beginning of the 40-year career of one of Australia’s most effective educators. Along with his fine education, he was a gifted musician, an inspired preacher and a talented artist. He dispensed medicines, extracted teeth, assisted visiting doctors, coached cricket, trained a choir and managed the football team! On 9 May 1885, he married an Aboriginal woman, Ada Cooper, and was accepted as one of her people. The skilled linguist honoured his new family by translating the Yorta Yorta language. In time, they honoured their gentle, dark-skinned Indian teacher by calling him ‘Grandpa James.’ When the Maloga residents were shifted in 1888 to the government reserve, Cummeragunja, Thomas reopened his school there. It was part of a system of reserves used to ‘manage’ the Indigenous population by training the children as rural labourers or domestic workers. He was told they should not receive more than three years of education, but he thought far beyond that. He petitioned the government for full education for all children. Thomas’s pupils reported he treated them as equals before God. He built their self-esteem speaking to them personally, making their school work a pleasure. He gave them the sense that they could succeed if they worked hard. They summed it up in two words, ‘He cared.’ In 1886, a local journalist reported about his school that ‘for all practical purposes the pupils are better educated than the majority of state school children’. Thomas became a quiet subversive. His classes weren't just for the kids. By candlelight at night he taught special classes for the adults of the mission. Using examples from his own background, he told them about Indians proving the pen was mightier than the sword in resisting the control of the British Raj. His granddaughter recalled, “He didn't talk about reading and writing, he talked about leading and writing.” The night school became known as ‘The Scholars Hut.’ From this unpretentious wooden building, the visionary Thomas launched his solo attack on the prejudice that said indigenous people were destined to remain ignorant. He gave skills to generations of Aboriginal activists including William Cooper, Doug Nicholls, Jack and George Patten, Margret Tucker and Bill Onus, as well as his own wife and son. He trained them to advocate with government on their own behalf – to have the confidence to speak in public, design eloquent petitions and write letters. It wasn’t long before Yorta Yorta men began writing to the governor asking for blocks of land they could farm for themselves. Thomas’s learning hub was the incubator of a crop of political activists who challenged government policies on Aboriginal issues and raised a voice of protest against Australia’s institutionalised racism. The Methodist lay preacher also fostered faith by taking Aboriginal people with him to ‘preach the Gospel of Salvation to the settlers on the Victorian side of the Murray.’ This helps explain why, for over half a century, Grandpa James’ graduates were bold in requesting the civil rights which the Bible said were the inheritance of all God’s children. When in 1909, the Aboriginal Protection Board arrived to take Aboriginal children from their families, Grandpa James would tell the children to run and hide. Later he would take them home to Grandma Ada and go over the lesson that day, because he didn't want them to miss out. He gave families courage to go on, assuring them they would fight later to get their girls back. Around this time the removal of Aboriginal farming blocks by the government fired Thomas’s sermons, so much so he was accused of inciting unrest. The Aboriginal Protection Board tried to sack him twice, but his outstanding record as a teacher quashed their efforts. Pastor Sir Douglas Nicholls had an illustrious career in the service of his people. In 1972 he was knighted and, four years later, he was made Governor of South Australia. When Thomas Shadrach James passed away in 1946 aged 87, his former pupil said of him, “He was indeed a good man. We native people sheltered under him. He was a Gandhi - a gentle man. In the last years, when things were bad and he tried to get better conditions for those on Cummeragunja Station, he did it by passive resistance. Among the people, he never favored anyone. All were treated equally. And there was never a word of criticism of him, by dark or white. He was loved by everyone.”

1 Comment

Sharon

3/2/2022 11:16:37 pm

How very interesting, Paul 🤩

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed