|

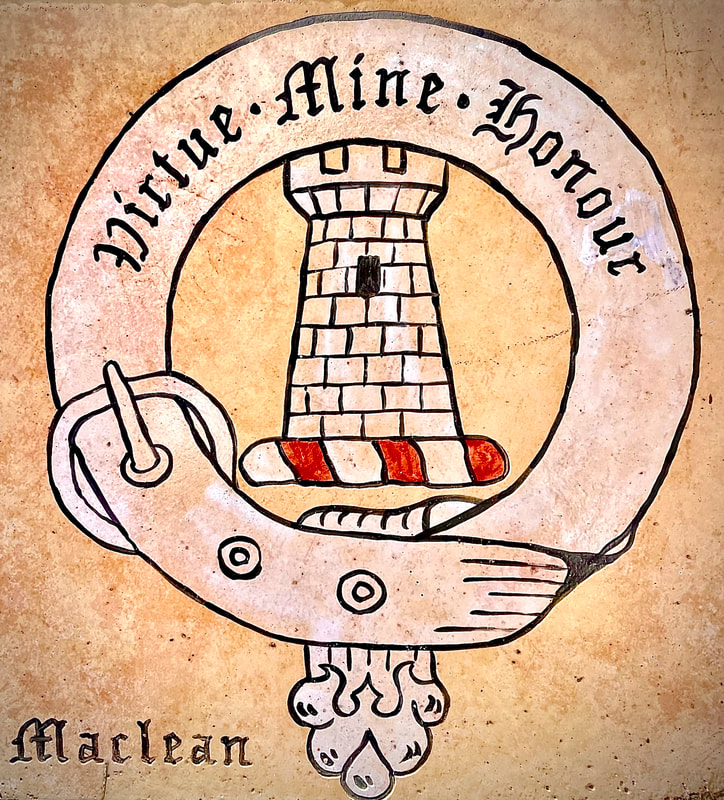

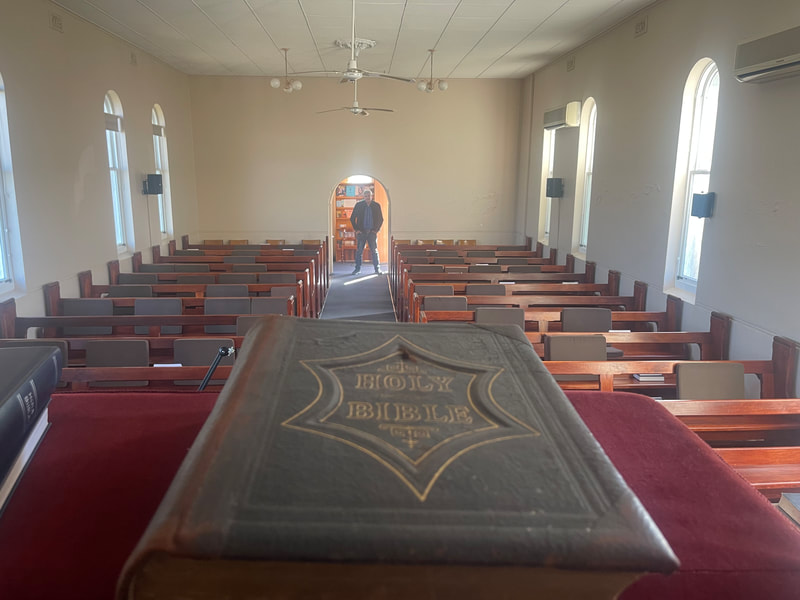

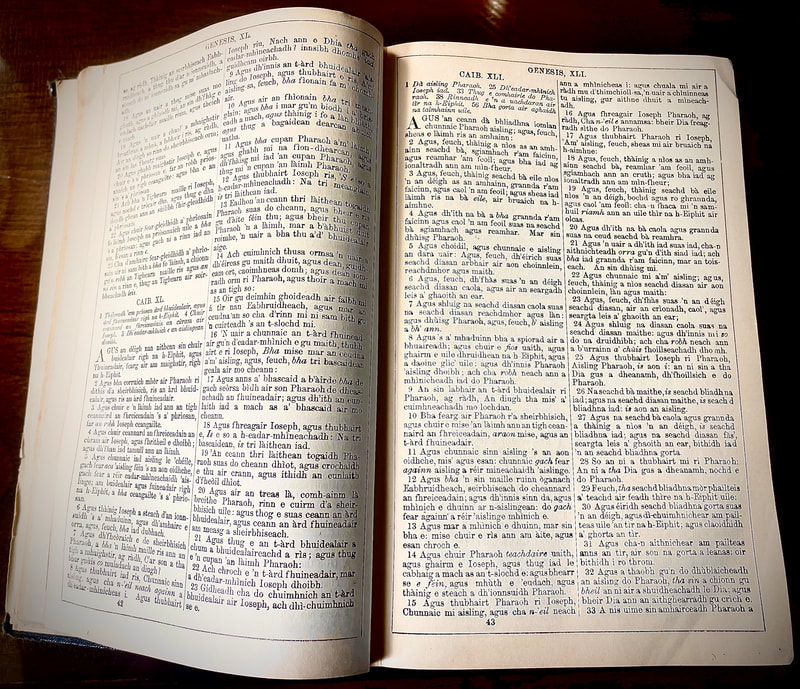

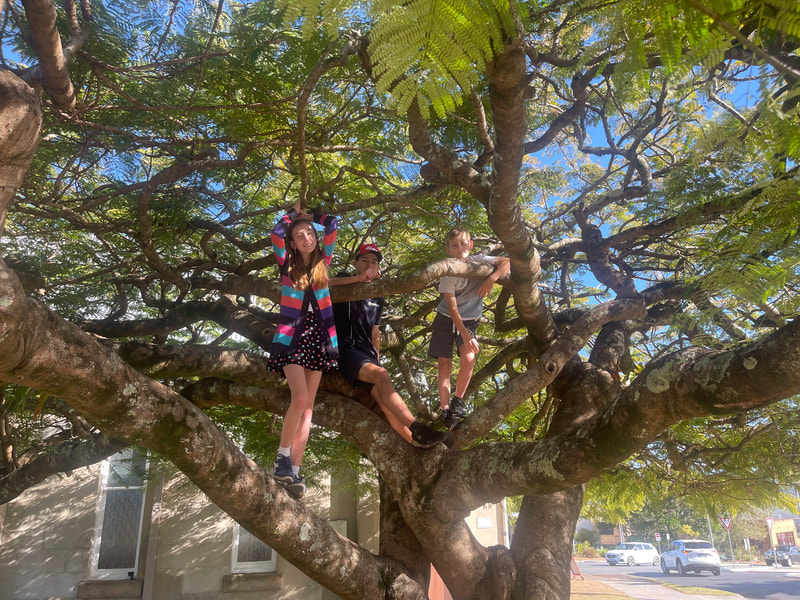

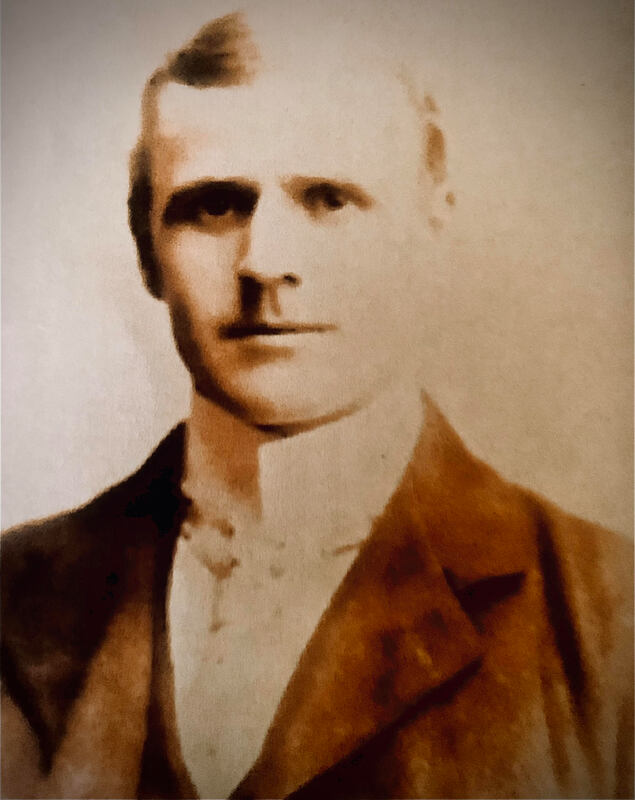

When you drive streets in Maclean lined with tartan telegraph poles and hear the skirl of the bagpipes echoing in the main street, you know the town is definitely a stronghold of Australia’s Scots history. And mine for that matter. Over two million of us claim Scots ancestry – my grandchildren have the blood of the Baird, Carey, Murray and McDonald clans in their veins. So, I spent a day or two there recently, looking under the ancestral kilt to see why big numbers of Scots moved here in the mid-1800’s. I was heartened to discover that the claim we Australians make for having one of the best lifestyles in the world, could well have been built on a bedrock of purposeful duty to God mined out of bare hills and heather half a world away in Scotland. An infamous chapter of Scots history came between 1820-40 when ‘the Clearances’ forced tens of thousands of Highlanders off their traditional lands into the diseased slums of Glasgow. The average life span of the men sank to around 40 years old. Severed from their clan stories, forbidden to speak their native Gaelic and faced with crushing poverty, many of them set sail for North America, New Zealand and Australia, hopeful of greater freedom and a chance to prosper. These refugees settled along the Northern Rivers of NSW. What struck me immediately was the fact that the first public structure they built in the Clarence River port of Maclean, was the Free Presbyterian Church. Clearly, for the Scots, their spiritual heritage was not baggage from the old world to be abandoned, but the cornerstone of the community they came to build. In today’s climate, that possibility is becoming considered outmoded, stuffy and even dangerous. I was encouraged by Scots journalist Jim Hewitson who noted that, though often seen as dour, lack-lustre wowsers, the Scots’ level headed application to the business of nation building, kept Australia on an even keel during the colony’s frenetic, formative years. “In business, education, medicine, banking, religion, law and politics the Scots, though small in numbers, exerted a strong and steadying influence.” (Jim Hewitson, Far Off In Sunlit Places, p.89) I sensed this was true of Maclean as I explored the museum full of ingenious hand-built machinery that drove the dairying, farming and fishing industries and generated commerce in the district. Dusty equipment, from the original school and hospital, spoke of the Scots’ hunger for good education and good health. When I learned they were known to print cards with the catechism (summary of Christian teachings) on one side and the maths times tables on the other, I knew they didn’t separate their faith from their children’s academic learning! ‘Dour’ was the word that came to mind when I stood beside our clan tartan pole musing on boyhood memories of my grandfather, Robert Baird. I can see him mowing our lawn in Sydney, formal in his waistcoat, watch-chain and polished boots. I can still hear his Scottish brogue as he reminisced about ‘the auld country’ and prayed aloud in church. I recalled seeing him arrive home late one night drenched in blood after intervening to stop a man beating up a woman on a lonely Sydney station. He had his face smashed in by a king-hit. I wondered, ‘What sort of courage did it take for an eighty-year-old man to do that?’ The Baird clan motto reads ‘Dominus Fecit’ – meaning something like, ‘we Bairds are successful through obeying the will of God.’ I knew the strength of my grandfather’s life was the faith he passed down through my mother, who lived out an intelligent, resilient Christian belief of her own. I feel our extended Baird tribe in Australia owe him and our Carey clan grandmother Jane for that gift. Looking back in history, I found a Braveheart who wore the Baird tartan. The poverty and upheaval in the early 1800’s set tens of thousands of freedom-fighters marching in Scotland demanding social justice, only to be met with a violent put-down. Nineteen of the leaders of ‘The Radical War’ were transported to Australia as convicts - two were sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. John Baird was one of them. On execution day 8th September 1820, thousands gave dignity to the scaffold at Stirling tollbooth as they sang psalms around him and Andrew Hardy for a solid hour. The two men told the crowd they were dying in the cause of Truth and Justice and plead with them not to head to the taverns to drown their sorrows, but rather to draw strength from their Bibles. That moment is now remembered every year at the Martyrs’ Monument in Sighthill Cemetery in Glasgow. In 2020, the Scottish Parliament voted that “the 1820 martyrs take their deserved place in history and that their sacrifices in pursuit of justice and fairness serve as inspiration to all those who share those values.” I left Maclean inspired by those threads of courageous faith woven into the clan tartan. Now, half a world away in Australia and two centuries later, I feel my duty is to keep these stories alive and to pursue justice and truth just as vigorously for the sake of future generations of Australians, many of them seeking sanctuary just as the Scots did. Judges 2:10 “After that whole generation had been gathered to their ancestors, another generation grew up who knew neither the Lord nor what he had done for Israel.”

2 Comments

Geoffrey Bullock

7/29/2023 06:55:58 am

Thanks for this, Paul! I did appreciate the verse at the end! A wonderful summary of the reason for your work!

Reply

Geoff, thanks. You’re right that this story was not just quarried out of my family history, but as I followed the threads, it spoke of the much larger picture of what’s happening in Australia. We’re forgetting to remember.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed