|

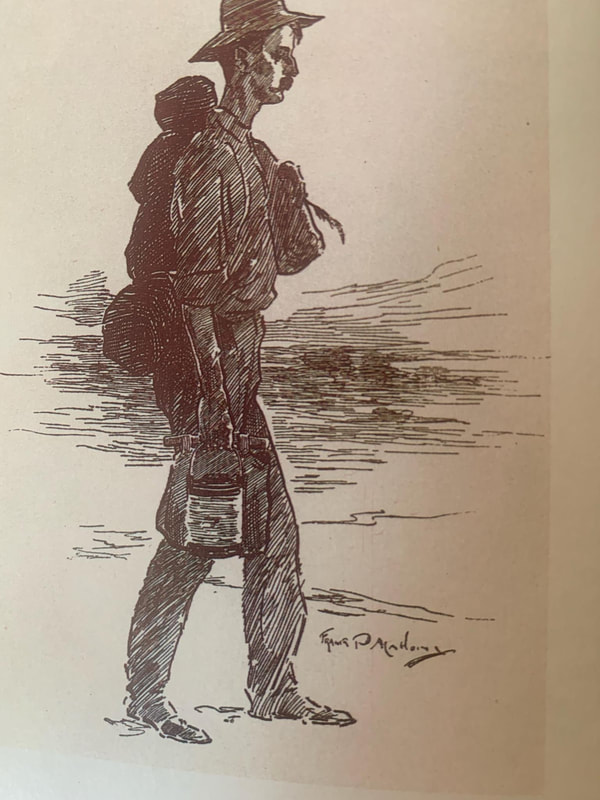

I’m headed out to Bourke for a wake this weekend. It’s to celebrate someone I consider an old friend – Henry Lawson. I’ve walked in the poet’s steps for four decades all across the Western plains, so I feel it’s right to go back to remember him. Professor John Barnes came on one of our Poets Treks and it rekindled his long-term interest in Henry. He wrote later, “It is no exaggeration to say that his one and only stay in what he and other Australians called the ‘Out Back’ was crucial to his development as a prose writer. Without the months that he spent in the northwest of New South Wales, it is unlikely that he would ever have achieved the legendary status that he did as an interpreter of ‘the real Australia’.” Henry died on September 2nd 1922 of a cerebral haemorrhage in Abbotsford Sydney a lonely, broken man. Sydney Morning Herald journalist Warwick McFadyen summed up his last years. ‘Australia’s greatest writer of the age was in and out of mental institutions and jail, a survivor of attempted suicide, an alcoholic destitute wandering the streets of Sydney. He was begging in the gutters, penning begging letters to other writers, and living on the care and charity of others.’ But Henry’s greatness as an interpreter of the Australian soul saw the Prime Minister and a host of notables follow his hearse through the streets of Sydney crowded with mourners as part of a State funeral, in spite of his failures.

I got to know Henry in the streets of Bourke and on outback tracks where he lived and worked and tramped during a nine month stay 1892-93. He was a budding writer then, one of the young men and women striving to speak in an authentic Australian voice for the first time. It’s agreed by critics that some of his most colourful characters walked out of his Bourke experiences into the imagination of the nation. They live on in 21st century Australia. Among them were hardy members of the Salvation Army who beat the drum and preached outside The Carriers Arms Hotel - a pub full of hard-drinking shearers and drovers. Lawson left a memorable picture of a pretty Lassie rebuking the rowdy circle of bushmen who were entertaining themselves by mocking and interjecting. “‘You ought to be ashamed of yourselves’, she said. ‘Great big men like you…drinking and gambling and swearing your lives away! Do you ever think of God or the time when you were children?’” Henry was amused that, following her arrival among Bourke’s toughest, the Salvos paper The Warcry had record sales and donations boomed. Despite his cynicism, you sense that Lassie’s challenge burned the consciences of these itinerants living rough and away from home. Watty Braithwaite, the Carriers’ rotund publican, was captured by Lawson’s pen, contentedly nodding off to sleep in his chair as the Army preached hellfire at him. Lawson asked tongue in cheek, ‘Has he not a fear connected with that warm place down below, Where, according to good Christians, all publicans should go?’ Flushed with enthusiasm for the mateship he found among men of the militant Shearers Union crowded into Bourke, Lawson declared the Salvos’ do-gooding wasn’t required in a place where the battlers sent round the hat for someone in need. But in later years, when he desperately reached for alcohol to overcome his despair, more often than not, it was the Army that rescued him out of the gutter in Sydney. In his poem Booth’s Drum, he admitted he had even got down on his knees and prayed with an Army lassie whose boyfriend had died in the trenches of Flanders. He confessed to her he once prayed to be saved. ‘You need a new ‘saved’”, she said. Lawson left a poignant picture of the Army praying for the complacent Bourke publican, with words that I suspect are a window into his own lost soul. It would take a lot of praying, lots of thumping on the drum - To prepare our sinful, straying, erring souls for Kingdom Come; But I love my fellow sinners, and I hope, upon the whole, That the Army gets a hearing when it prays for Watty'ssoul. A few years back, here in Dubbo, a Cornerstone student astonished me by revealing she was Watty Braithwaite’s great-grand-daughter. I wondered at the time, ‘Is it possible the Army’s prayers brought her here?' Henry included the wistful hope in his poem, Now I often sit at Watty's when the night is very near, With a head that's full of jingles and the fumes of bottled beer; For I always have a fancy that, if I am over there, When the Army prays for Watty, I'm included in the prayer. At about the same time as Henry wrote this, in a tough mining town near Armidale, it was a Salvation Army Lassie who gave hope to my grieving grandparents. Their infant son had died of diphtheria and the good news of Jesus that she told them, transformed my family. So, as I head out to Bourke this weekend to salute ‘the interpreter of the real Australia’, I’ll make a point of standing outside The Carriers Arms to salute those uniformed men and women he met, who beat the drum and prayed for the souls of the men and women of the outback.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed