|

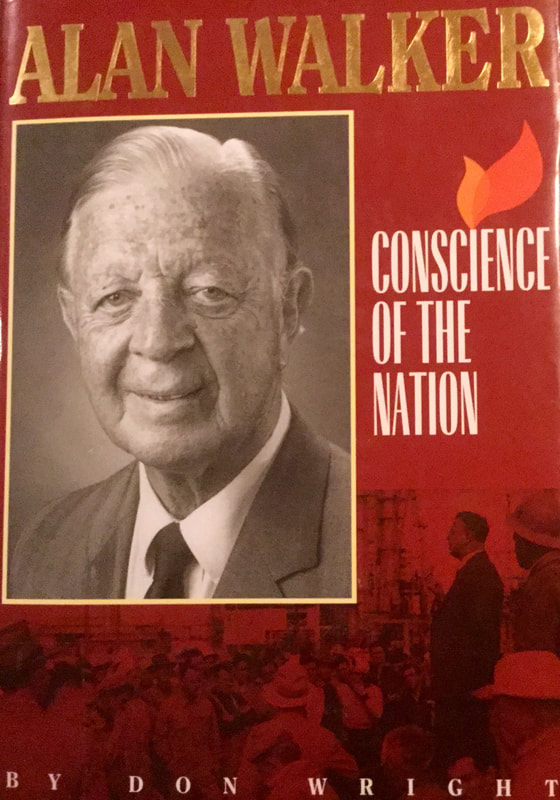

The scene is a small house set between the sea and the Australian bush. Picture a lone man wrestling in prayer between tall, white gumtrees in the moonlight. It’s 1953 and the country is just beginning to recover from the battering of war. The forty-two-year-old Methodist minister’s name is Alan Walker and he’s full of fear at setting out on a nation-wide mission. His convict ancestor had arrived in Botany Bay in 1810 and 20 years later, through the preaching of a travelling Methodist, his alcoholic son John decided to follow Jesus and began preaching in the Windsor district with powerful effect. And now his great-great grandson Alan - the thirteenth evangelist from that line – is praying for strength. A sudden rustling of the gum leaves in the night-wind made his spirit soar. A vivid image of Jesus challenging Rabbi Nicodemus to allow the wind of the Holy Spirit to flow through his life, gave the shrinking preacher the courage he needed to undertake the preaching ministry to his native country, half a world away from Israel. His preaching had a powerful effect – just as his great-great grandfather John Walker’s had in Windsor 150 years previously. Decades later, Labor parliamentarian Bill Hayden dubbed Alan Walker, ‘The Conscience of the Nation.’ Others called him ‘Mr Methodist.’ What did that mean? There is strong evidence that the 18th century Methodist movement, launched by Rev John Wesley among the oppressed working people of England, did a great deal to steer the country past the worst excesses of bloody revolution that swept the European Continent for decades. The Methodist field-preachers set a bench mark in fighting social evils – countering the abuse of alcohol and caring for the poor, the prisoners and the slaves.

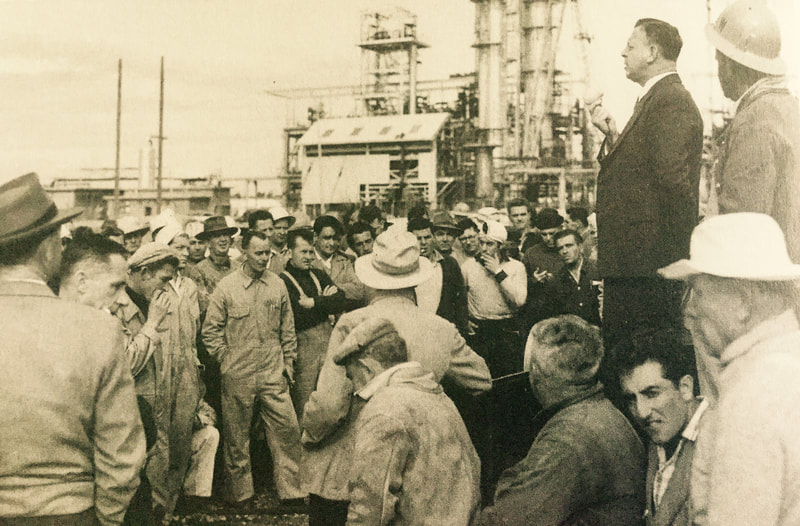

Someone said they made compassion fashionable. In 19th century Australia, more often than not, it was Methodists who led the campaign for better working conditions. I saw evidence of it in the seven Methodist chapels scattered through the tough mining town of Broken Hill when I lived there. Alan Walker was the Aussie John Wesley. He was convinced that a true follower of Jesus should be concerned with the whole of life, busy at improving the lot of his fellow man in this world, as well as preparing him for the next. For fifty years, the wind he had heard in the gum trees sustained Alan Walker’s prophetic voice, calling out the best in the nation and warning Australians against neglecting faith in God. Like Wesley, his genius lay in choosing accessible locations to speak out on issues. He used plain language that Aussies understood. He had a simple philosophy that took him to the beaches and into the streets and workplaces. “I ask the question, ’What does it do to people?’ I am against racism because it destroys human dignity and freedom. I am against war, alcohol and licentious sex for the same reasons.” Alan publicly opposed the Vietnam War and was twice thrown out of South Africa for denouncing Apartheid. His innovations for getting to the common man were endless. He broadcast his message in the media. Throughout the 1950’s he wrote a column for The Sydney Morning Herald. In the early days of television, his show Challenge the Preacher, filmed on locations like Bondi Beach and the Everleigh Railway workshops, attracted an audience of half a million. The cabaret dances he held for teenagers in the 60’s shocked more conservative church goers. His evangelist’s heart saw it as a way of engaging the rock ‘n roll generation with the deeper beat of the gospel. In 1971, he entered the world of hippiedom, flower power and ‘Jesus freaks’ by launching the Newness NSW campaign. As the head of the Methodist Central Mission, he engineered ethnic congregations, the Vision Valley conference centre, residential hostels, a training college to equip young people from Pacific nations for ministry, a school for seniors and a singles' society. In 1963 he received a call from a distressed man who later took his own life. Determined not to let isolation and lack of support be the cause of more deaths, Alan launched a 24-hour crisis support line called Lifeline that has inspired telephone counselling services around the world. Sir Alan Walker received widespread recognition and public honours. Whether people liked him or not, Sir Alan Walker was admired for his readiness to stand beside the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, no matter the personal cost. To my mind, this made him a knight in the truest sense. But the feisty evangelist was always adamant about the real purpose of his work. “Let it never be forgotten that it is Christ we offer,” he said. “The Church must never degenerate to being akin to a government or social service agency.” On the wind, across three centuries, I can hear the voice of another maverick field preacher – John Wesley – uttering a loud, ‘Amen!’

2 Comments

Geoffrey Bullock

8/13/2022 08:16:46 am

Love the quote "Let it never be forgotten that it is Christ we offer... The Church must never degenerate to being akin to a government or social service agency.” That is the right balance in bringing the Kingdom of God to all of creation!

Reply

Kev Murray

8/13/2022 08:55:09 am

Great and inspiring insight, thanks Paul.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed