|

Native-born John Tebbutt has his name written on the moon alongside famous thinkers like Copernicus, Pythagorus and Tycho Brahe, but in all his eighty years he hardly moved more than a few miles out of the Hawksbury District near Sydney. Born in 1834 and growing up on farm near Windsor, the young lad found joy looking into the star-filled Southern skies at night. At school, his mind was set toward the heavens by his teachers – all men of intelligent Christian faith. A passion for astronomy was lit in his five-year-old heart by Edward Quaife, the long-term teacher at the local Anglican parish school. At nine years old, he went to the nearby Presbyterian school to learn from Rev Matthew Adam, a sturdy Scot who worked as a missionary among seamen in Port Jackson. John’s teenage years were spent with Henry Stiles, an evangelical clergyman chosen to come to Australia specifically for his ability to train young people. This classical scholar taught him Latin and the higher mathematics he needed to sustain his longing to unravel the mysteries of the heavens. John finished his education aged 15 and went to work on his father’s farm. In his spare time, he worked on improving methods of farming and learning German and French. Together, these mentors instilled a warm Christian faith into their pupil, which explains John’s lifelong commitment to energetic organisations in Windsor like the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Bible Society. They also fashioned a reasoned understanding of Science and the Bible into the twin pillars of John Tebbutt’s life. It began with his boyish interest in steam engines and clocks that rapidly reached for the skies as he grew. As an older man he explained, “It dawned on me that the universe was really a mechanism of the highest order and being mechanically inclined, I began to turn my attention to the celestial mechanism.”

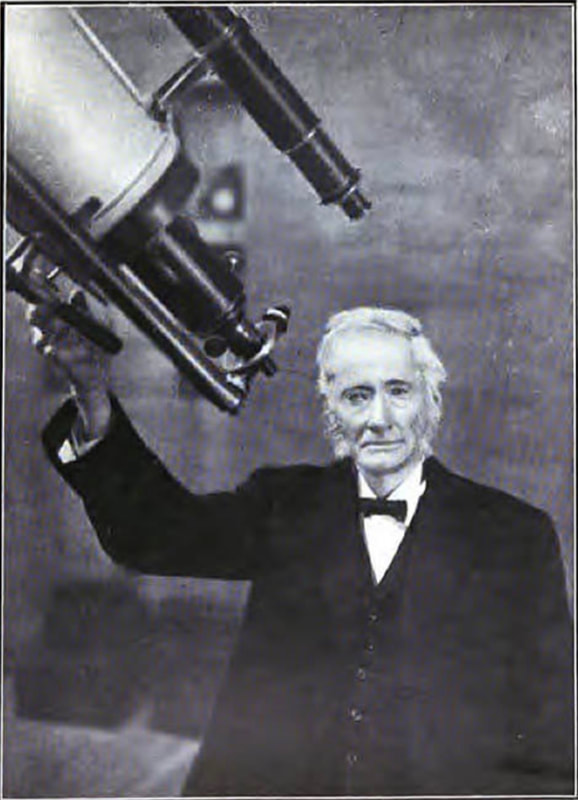

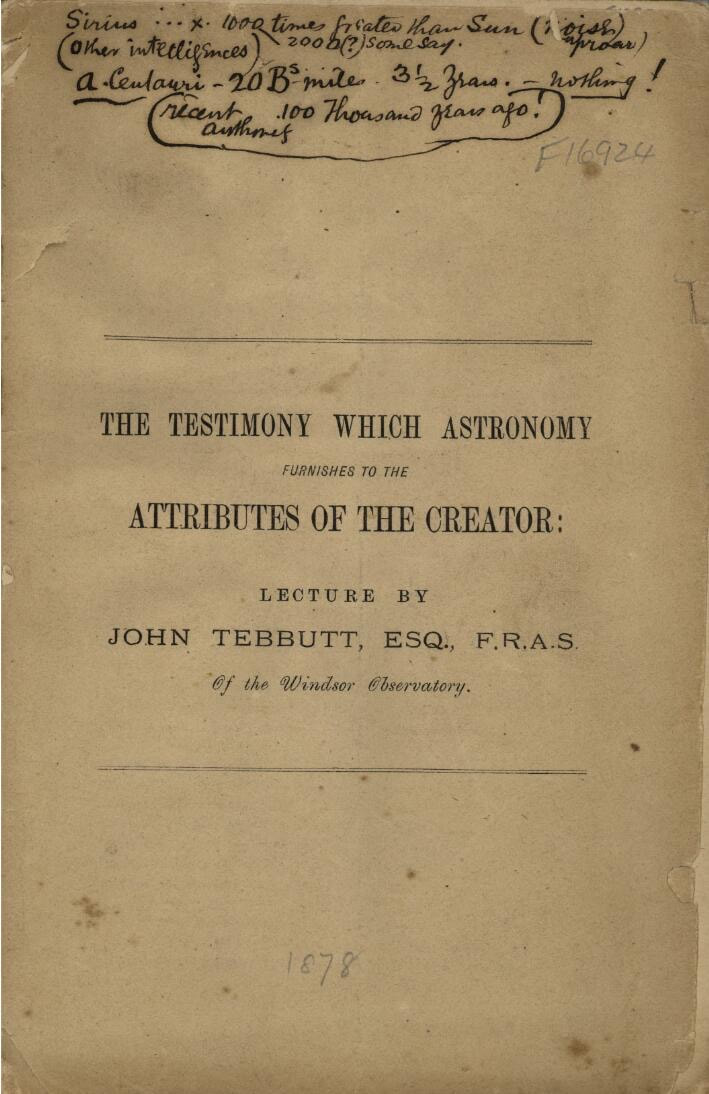

By the time he was 19 years old, with advice from John Stiles, a retired Royal Navy midshipman and brother of his tutor, John set out on his exploration of the vast, star-filled dome of sky above him. Picture the eager amateur setting to work with just a sextant, a grandfather clock and an ordinary marine telescope, making his complex observations with no real outside help. In May 1861 aged 27, John was the first to log the arrival of one of the greatest comets in history, months ahead of experienced astronomers in the Northern Hemisphere. He quietly announced the event in a paragraph in the Sydney Morning Herald, but this non-professional astronomer, working with the humblest of instruments, had made an indelible mark in the world-wide scientific community. John had a special interest in comets because he was fascinated by the marvellous accuracy with which they obeyed mechanical laws. This evidence of design inspired his working life and in November 1861 he purchased a 3 ¼ inch telescope with which he observed Encke’s comet. He was proud that his was the smallest telescope of 27 used across the globe to track Swift’s comet in 1862. There seems to have been an independent streak in the Tebbutt family. John’s grandfather was one of the first free settlers to make the risky 10,000 km journey for a fresh start in NSW. So, it’s no surprise to hear that his grandson, like a true native-born ‘currency lad’, turned down the offer to be Government Astronomer at the Sydney Observatory, preferring to use his own equipment at rural Windsor. In 1863, he got on the tools and worked as carpenter, bricklayer and slater to build an observatory to house his Telescopes. He then bought a 4 ½ inch model in 1872 and an 8 inch in 1886 to expand his reach. John applied the same rigorous spirit to his research. Step by patient step over the next 65 years, he kept a meticulous record of his findings which he published in 350 articles in scientific journals. He made a career out of searching for truth and he simply could not stand shallow thinking that appeared sham or make-believe. He argued,”The truth shall make humanity free whether it be religious or scientific and we scientists have to fight for that freedom The silver medal at Paris Universal Exhibition in 1867, being made a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1873 and then the award of the prestigious Hannah Jackson gift and medal in 1905, were indications of his high standing in the international scientific community. His self-funded, home-built, star-gazing outfit was eventually listed as one of the principal working observatories in the world. At a time in the 19th century when the Church and Science were fighting fierce battles about origins, some in the religious community doubted John Tebbutt could have a foot in both camps. But the eminent scientist never left the fellowship of St Matthew’s Windsor where he had been tutored, nurtured, confirmed and married. In 1878, John was probably the best qualified man in the country to deliver a clear declaration to young men at the Windsor YMCA on the evidence he had found of the Creator’s fingerprints from his study of the universe. In 1976, John Tebbutt and his observatories were chosen as inspirational images put on Australia’s original $100 note. It’s clear he was chosen because he was one of those brave explorers with the faith to attempt what seemed impossible. His contemporary, poet Robert Browning, captured that spirit with his line, “Ah, but man’s reach should exceed his grasp or what’s a heaven for?” John’s most significant memorial though, is not found on a bank note, but in the church that was his spiritual home. St Matthew’s was commissioned by Lachlan Macquarie, a visionary Governor influenced by his wife’s evangelical faith. The beautiful domed apse is its main feature. Beneath its four arches are inscribed statements foundational to John Tebbutt’s carefully constructed worldview – the Lord’s Prayer, Exodus 20, the Ten Commandments and the Apostles’ creed. The secret is in the ceiling - painted in the graduating shades of blue that John loved in the Southern sky. Locals will tell you the touching story that on one particular evening, a member of their congregation lay on the floor of the apse staring up, just as he had as a boy out on the farm. And with perfect precision, that local, home-grown astronomer positioned gold stars in the vault where they stood on that very night. That artistic statement has got to be John Tebbutt’s most powerful legacy. It echoes the conviction of another man who had slept out under the stars as boy, 3000 years earlier. He’d written it into a poem that began, “The heavens declare the glory of the Lord, the skies proclaim the work of his hands.’

4 Comments

John Gibson

1/24/2023 11:02:46 pm

Great story thanks Paul... John Tebbutt is an inspiration

Reply

Trevor Storey

1/25/2023 12:08:55 pm

It’s great story!

Reply

Steve Hembry

6/27/2024 04:25:55 am

Thanks Paul. Even ‘Yogi Bear’ would be cheering.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed