|

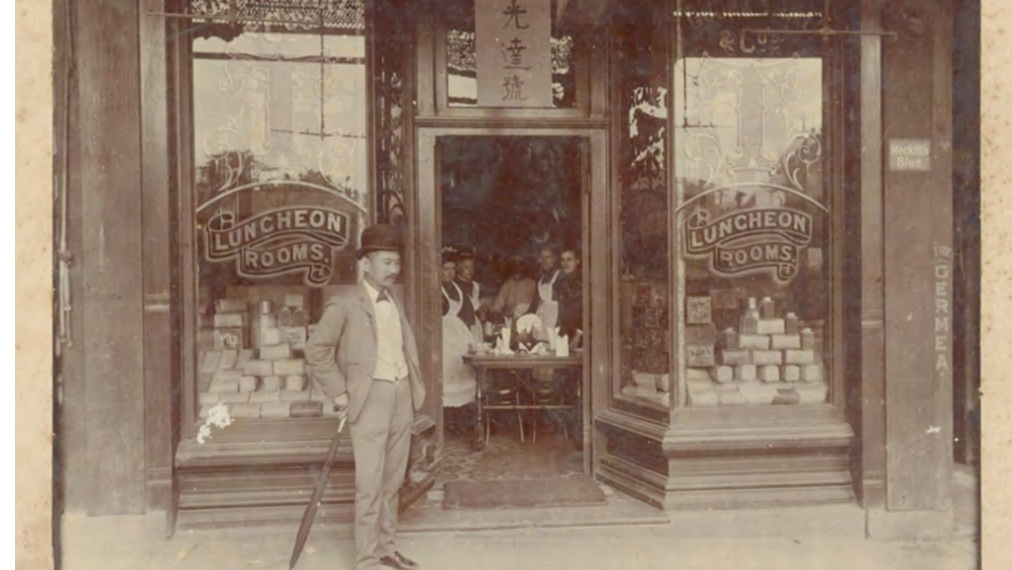

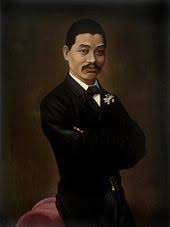

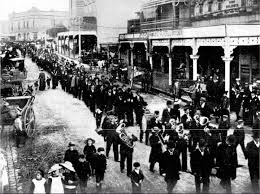

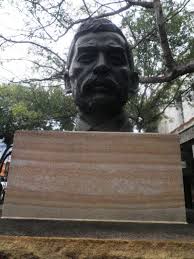

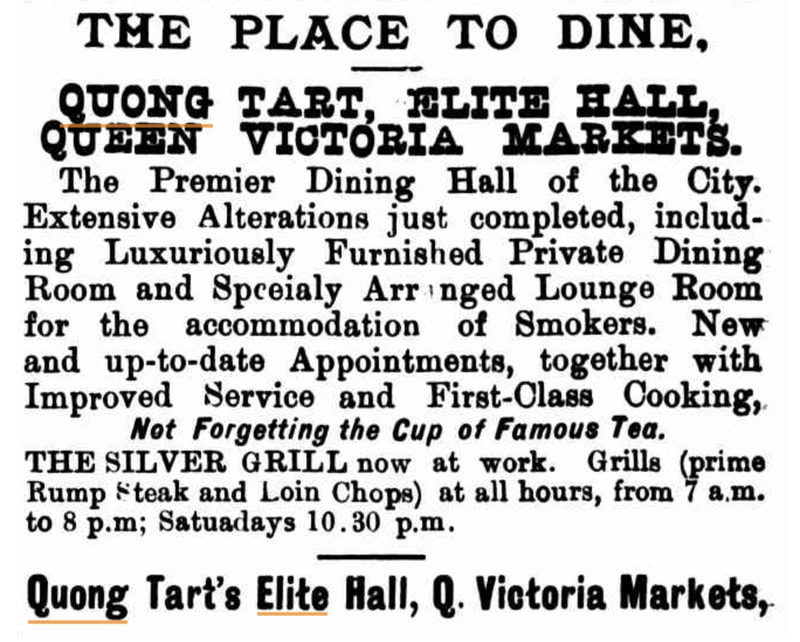

Sydney in the 1890’s. Picture a Chinese man with a broad Scots accent, quoting Robbie Burns poems with gusto to appreciative audiences of Sydney’s leading citizens. He might pump out a skirl on the bagpipes! Mostly he appeared in public dressed as a dapper English gentleman, but on special occasions, adopted the full regalia of a Mandarin of the Fourth degree granted him by the Chinese Emperor. As I read the story Mei Quong Tart, I became convinced he must be one of the most extraordinary characters in Australian history. Arriving with a band of coolies on the goldfields at Braidwood in Southern NSW in 1859, nine-year old Quong Tart quickly adapted to his new surroundings by picking up the language, poetry and music of the Scottish miners. The wealthy Simpson family took an interest in the eager lad and advised him to invest in gold mines. By the time he turned eighteen, he was the wealthy employer of a team of men and an advocate for the Chinese on the diggings. Before long he was playing cricket, sponsoring race meetings, elected a member on the local school board and helping to build an Anglican church. He was naturalised in 1871. READ MORE ... (image courtesy of Society of Australian Geneologists) The turning point in his life came when his mining business failed and he fell into a depression. In a book given him by Mrs Simpson, he read the story of Joseph, who had been sold into bondage and passed through many hardships in a strange land amongst a strange people; but who had risen to be an influential man in Egypt. He later told his wife he fell asleep, but woke up with a start, because he thought he heard someone speaking to him— 'Courage, Quong Tart; you shall yet be great.' The ancient Biblical story of Joseph became the template for his future. He felt God had put a call on his life. His business recovered and the Simpson family introduced him to influential people in Sydney. In 1881 he left for China carrying letters of high commendation from the NSW Government, Presbyterian, Wesleyan, Anglican church leaders, his employees, fellow Merchants and Masonic Lodges. He returned to Sydney to launch a chain of high-quality tea shops that took him into the upper levels of society. In 1886 he married an English woman, Margaret Scarlett who later wrote his biography based on press clippings of his life – ‘How a Foreigner succeeded in a British Community.’ Quong Tart forged his path at a time of extreme anti-Chinese sentiment in the colony. The Bulletin magazine in 1886 adopted the masthead ‘Australia for the White Man’ and published a cartoon of a sinister Chinese octopus strangling white Australians with tentacles labelled with things like OPIUM and PROSTITUTION. Remarkably, three years previously, the Chinese businessman had approached the government with the first of many unsuccessful attempts to have the importation of the drug banned. He hated opium addiction with a passion – he believed it marred the image of God in his creatures. Research trips across the goldfields helped him ascertain the extent of the problem first-hand. When he spoke, he reminded his fellow citizens that it was England’s East India Co that had cynically used opium to force China’s door open for trade and thus triggered the addiction problem. In 1887, he revived the anti-opium campaign with a second petition to parliament. It was an articulate case for banning the substance, arguing that addicts could recover and become effective community members with help from Chinese clergymen. His rousing speech to a packed Pitt St Congregational Church in 1894 brought the cheering audience to its feet. Quong Tart worked tirelessly to build a bridge between his two cultures. He was an advocate for the rights of Chinese-Australians and served as an interpreter. He was a prominent member of the Chinese Commercial Association. When anti-Chinese sentiment flared, he spent much time defending his countrymen. He was also able to soften the bitterness on the part of the immigrants by helping them to understand how this antagonism came about. He sent a petition in his own name requesting that the Chinese government raise the issue of maltreatment of Chinese residents in Australia with the British government. He was also part of the NSW Royal Commission on Alleged Chinese Gambling and Immorality and Charges of Bribery Against Members of the Police Force from 1891 to 1892. But it was mostly his kindness and generosity of spirit that earned Quong wide respect. He expressed his passionate commitment to the teaching of Jesus in practical ways, caring for the underprivileged and defending the weak. He organised endless charitable functions under the patronage of the Governor and his wife, providing dinners, gifts and entertainment at his own expense for the aged and infirmed and for members of Sydney’s aboriginal community. Two hundred and fifty newsboys were gathered off suburban streets for a meal in his restaurant where he urged them to make something of their lives, believing ‘they might possibly become the future leaders in our State.’ He helped clothe and feed the children of the Waterloo Ragged School and undertook many other efforts to alleviate the plight of Sydney’s poor. The railway and tramway workers were guests at his tearooms. Leprosy sufferers were repatriated to their own families in China through his generous efforts. Quong’s faith found expression in progressive ideas about Sydney social politics. His tea rooms were the site of the first meetings of Sydney's suffragettes and he devised new and improved employment policies for staff, such as paid sick leave, reasonable hours, meals in the restaurant and free time for reading and needlework. He said that, 'not through antagonism to each other, but through affection for each other,' would the best work relations be gained. Employees were not looked upon as mere machines, they were men and women with souls and were treated as such. Quong Tart created amusement wherever he went and people responded warmly to his sparkling sense of fun and constant good humour. It was not surprising that he made his trademark two hearts, closely interwoven. As businessman, it was noted that Quong was exemplary in blending the astuteness of the man of the world with high Christian principles. His commitment to excellence was carried into the magnificent fitting out of his shops where good food was served at affordable prices. The best of everything was lavished on the customer and employees were instructed to treat rich or poor alike. Following the Bulli Colliery disaster in 1882, he threw himself into funding relief operations for miners’ families. As a cultural benefactor, he also promoted concerts and exhibited the work of local painters at his shops and he encouraged all kinds of sport. When it came to church life, Quong stepped easily over boundaries. Though a zealous Anglican all his life, he had his children baptised and educated in different denominations to avoid appearing prejudiced. He supported all kinds of Christian missionaries and home-workers and entertained Anglican, Methodist and Presbyterian clergy alike. It seems that General and Mrs Booth met him and may even have tried to persuade him to join the Salvation Army! He was instrumental in founding a Chinese Anglican church in Sydney. In 1902, Sydney’s extraordinary Chinese benefactor suffered a brutal attack from an intruder in his Queen Victoria Building office. He never fully recovered and died of pleurisy some months later in 1903. 1,500 mourners, drawn from every section of society, listened to his Christian burial service read in Cantonese by a Chinese clergyman. You wonder if they felt Quong Tart had, singlehandedly, raised a large question mark against the newly legislated ‘White Australia Policy’. It was declared at his funeral that, ‘as a Christian he kept his life unsullied. His life was instinct with the highest ideals, the Brotherhood of Man and the Fatherhood of God. In his belief in these he never wavered.’ His wife Margret said her husband lived out the Quaker principle: “I expect to pass through the world but once; if, therefore, there can be any kindness I can show, or any good things I can do, to any fellow human being, let me do it now, for I shall not pass this way again.” A commemorative bust of Mei Quong Tart, the first Chinese immigrant to gain full acceptance in the Australian community, was placed in his home suburb of Ashfield in 1998. His mansion was later converted into a nursing home, bearing his name and exists today with a chaplaincy service, catering for the spiritual and cultural needs of ageing Chinese.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed