|

I was on the hop between the Central West and the South Coast of NSW listening to eminent historian Tom Holland paint a graphic picture of the ancient Persian Empire and the power and glory of its kings. It was nothing short of epic! Oddly enough, I was expectant as I wound down the Western escarpment of the magnificent Kangaroo Valley, that I’d find a story. I read that George Evans, the first European explorer looking down from the heights, had exclaimed it was ‘a view that no painter could beautify.’ Sure enough, tucked away in an unlikely corner, there it was. Housed in a bush museum, nestled beside the fine sandstone suspension bridge, I found a tiny essay on the major shift in Australia’s colonial history, when ‘settlerism’ replaced the era of convict reform. It began in the 1820’s as immigration from the crowded industrial cities of England and Scotland, along with escapees from the Irish potato famine, increased. Historians say that many of these folk who adventured 16,000 miles were optimists who came ‘looking for a life as well as a living.’ Their dangerous journey has been described as playing ‘migrant roulette’ with their children.

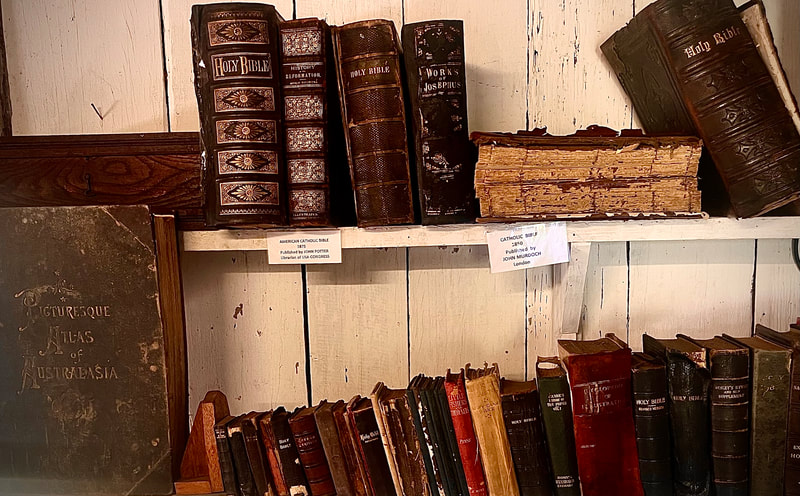

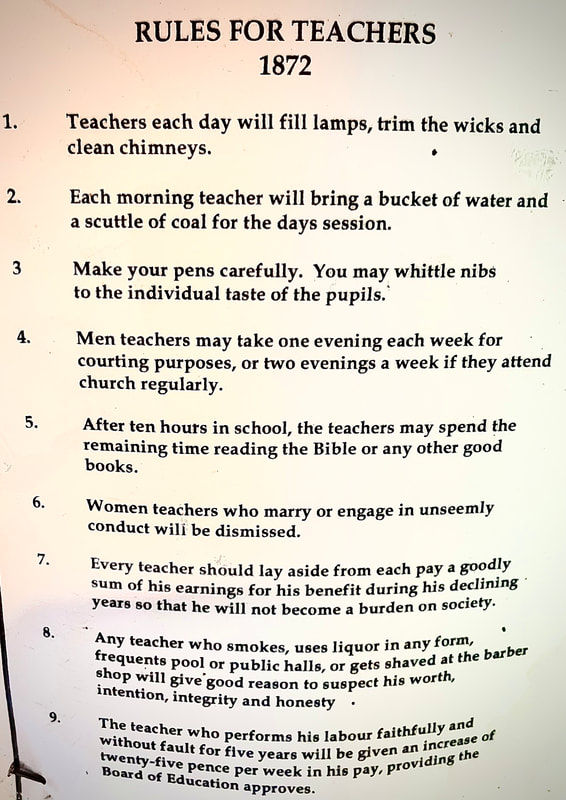

In my photos of the museum’s collection from early homes in the district, I saw evidence of Jesus’ influence in all sorts of ways. The love for design is everywhere. It’s in the practical cooking implements, carefully kept tools, intricately crocheted cloths, well-turned furniture. In a real way, I think they were trying to add to the beauty of the Valley. The reverently fashioned communion chalice and the polished organ were eloquent statements about the spiritual life of the scattered farming community. More than anything, the shelf-load of leather-bound Bibles suggests these ancient faith stories were the valued bedrock of families throughout the district. Mostly I suspect, it was the mothers who gathered the children to listen to the Good Book. Schoolteachers were expected not only to read it, but to teach it and attend church regularly. Looking at the faces of the sizeable contingent of young men who rode away to war in 1914, I knew they read the New Testaments they carried in their pockets into the trenches of Gallipoli and France. My travelling companion Tom Holland, who wouldn’t call himself religious by any means, has argued forcibly that, in spite of its many flaws, Christianity has been ‘the most influential framework for making sense of human existence that has ever existed.’ What is remarkable is that, after a lifetime of study, he credits its success not so much to power-brokers and religious hierarchies, but to humble women who systematically embedded the biblical narratives in their children. ‘The Christian revolution’ he suggests, ‘was wrought above all, at the knees of women.’ Some would say it was just a fusty museum full of old stuff, and I get that. But I left feeling that those humble items were lines in a significant chapter telling of a quiet revolution, led by ordinary folk, in an obscure corner of the world. ‘The conspiracy of the insignificant’ someone has called the world-wide movement of men and women who have followed Jesus. Mothers and fathers teaching their kids from the Bible. Not always, but often enough, this homespun faith had a softening effect on the hard-edge of European settlement that impacted on the Aboriginal people. The Wodi Wodi tribe had long believed that Kangaroo Valley was a place of healing. I drove away certain that the hopeful message of Jesus had added to that and could help it remain so.

1 Comment

Aly

10/7/2023 02:11:20 pm

Wow, that's am interesting observation from Tom Holland about the role of women in "the Christian revolution".

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed