|

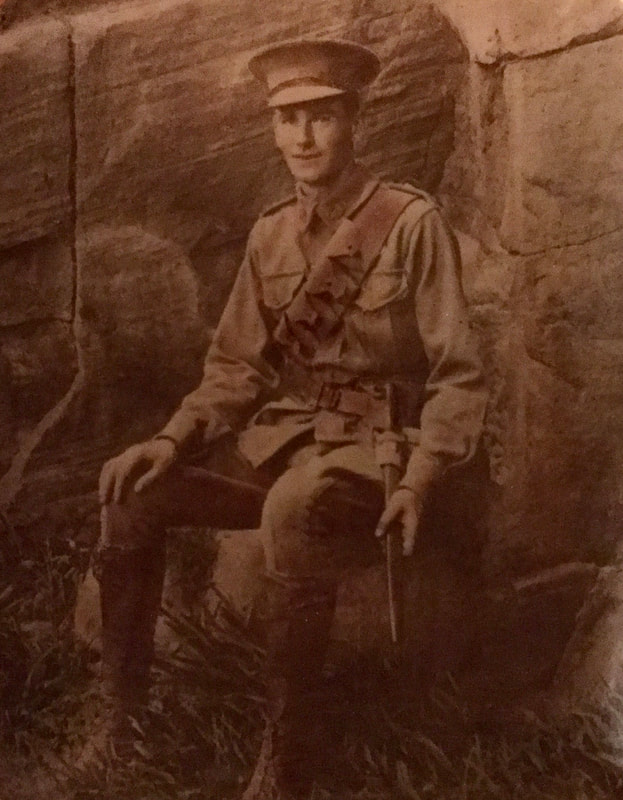

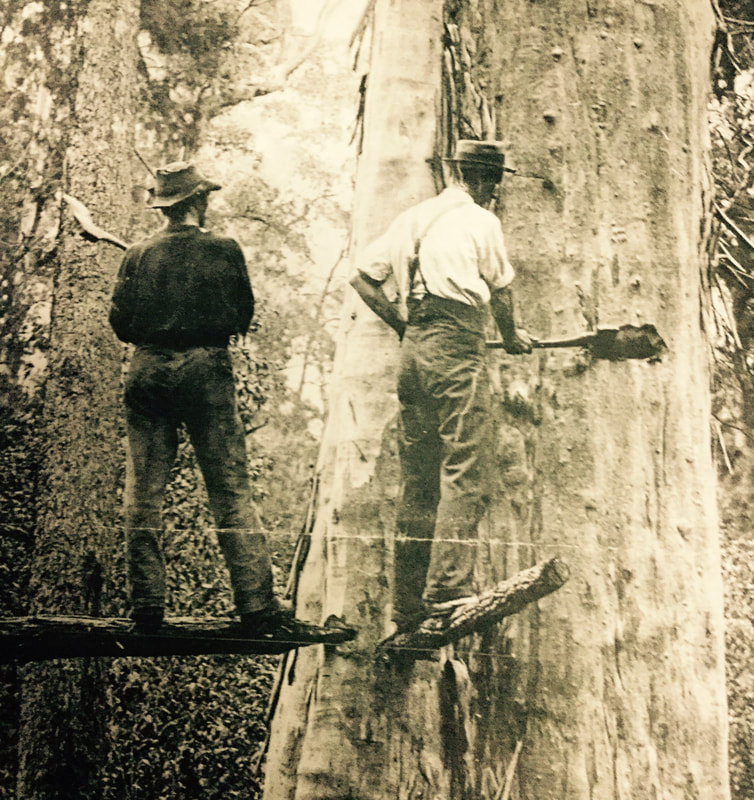

On the NSW North-Coast, in the sleepy little town of Kendall, a solitary ANZAC soldier stands sentinel over the memory of some local lads. They were husky young men, familiar with challenges - axemen, sleeper cutters, bullockies and drovers. Following the declaration of war in 1914, they marched away down the hill, through the gums, crossed an ocean and found themselves half a world away, caught up in a massive conflict they knew little about. On the NSW North-Coast, in the sleepy little town of Kendall, a solitary ANZAC soldier stands sentinel over the memory of some local lads. They were husky young men, familiar with challenges - axemen, sleeper cutters, bullockies and drovers. Following the declaration of war in 1914, they marched away down the hill through the gums, crossed an ocean and found themselves caught up in a massive conflict they knew little about.

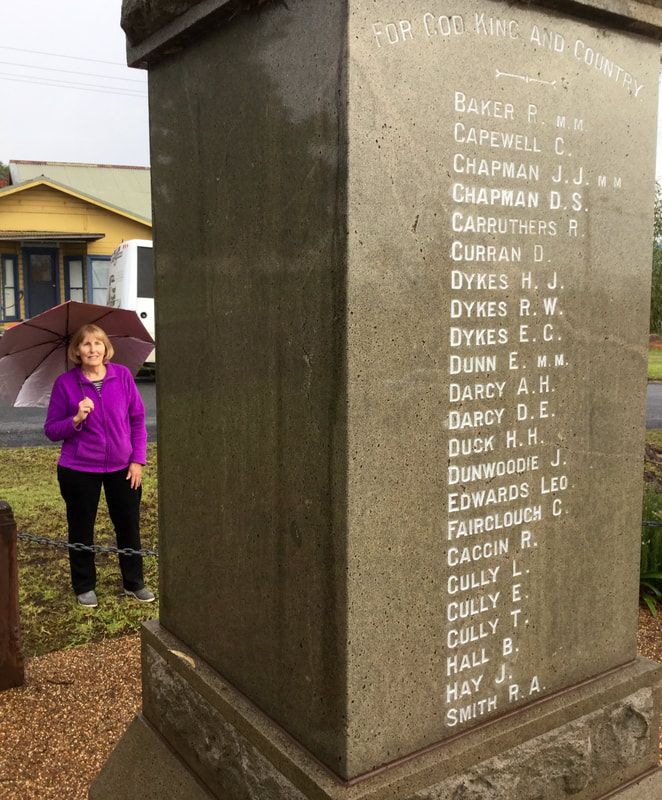

The polished granite pillar is the symbol that quietly links their bravery to the larger myth that still haunts Australia. After the guns fell silent in 1918, they said it was ‘the war to end all wars’. But a century later, redemptive violence continues to escalate and all around the world, young men and women are being relentlessly consumed by armed conflict. The last twenty years of Australia’s military commitment in Afghanistan hasn't eased the heartbreak in that country. Recently, not a stone’s throw from the cottage her mother grew up in, my wife Robyn found the names of family - the four Dykes brothers who saw action at Gallipoli and France. The gold letters carved into the granite shrine say they fought with honour for God, King and Country to bring us Freedom. One of the brothers remained buried in French soil. A hundred years down the track, how can Australian families measure the cost of that War - the lost lives, shattered bodies and scarred minds? Did it honour God? Are we really free? A short walk down Albert street, outside the Catholic Church, stands another symbol - one that turned the ancient rite of redemptive violence upside down. It's a reminder that one day, just thirty lifetimes ago, Jesus, the young country carpenter, walked away from his family in Nazareth to die in agony on a wooden cross designed by the occupying Romans to dehumanise their victims. That's why, half a world away, Kendall’s three metre stone cross now stands quietly in the local churchyard. In ten thousand small Australian towns, other such crosses stand as symbols of hope. They celebrate the victory of a King who laid down his life to win true freedom for the people of every country.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJoin The Outback Historian, Paul Roe, on an unforgettable journey into Australia's Past as he follows the footprints of the Master Storyteller and uncovers unknown treasures of the nation. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

Sponsored by

|

Privacy Policy

|

|

Copyright 2020 by The Outback Historian

|

Site powered by ABRACADABRA Learning

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed